Dairy Farmers, It takes longer in the morning. Especially on a morning like today: It’s the first working day for dairy cow 190. The day before she had her first calf, the milking equipment is scary for her, the routine of her colleagues is missing.

Katharina Leyschulte puts her hand on the cow’s flank to calm her down.

“Farmers always put the new ones between particularly experienced cows, that gives security,” she says, placing her to-go mug next to a bulky construction site radio. She still has to disinfect a total of 140 cow udders, pre-milk them by hand, harness them up and then wipe them off with lukewarm water. Without caffeine and pop songs, that’s just after six. “We basically built the milking parlor around the coffee machine,” says Leyschulte, wearing a floor-length blue apron and grinning.

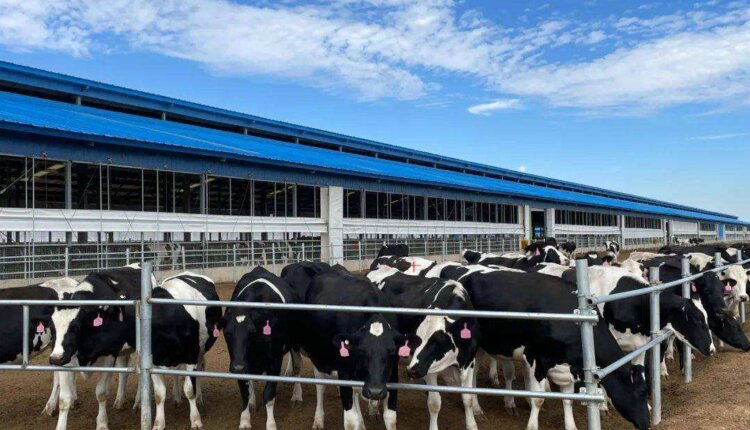

Katharina Leyschulte is 29 years old and one of tens of thousands of dairy farmers in Germany. Your farm is in the Münsterland region, just a few hundred meters from the Lower Saxony border. In August, visitors have to make their way there off the country road through a vast maze of cornfields. At the end of the street, three large stables rise out of the sea of pistons, next to a sandstone-colored farmhouse.

In addition to fourth farmers generations of the Leyschulte family, hundreds of cattle are at home here: 140 dairy cows, almost as many young females, a handful of bulls and more and more calves.

The farm has a long history. Almost 100 years ago, Katharina Leyschulte’s great-grandfather led the first cows into the barn in this extreme corner of North Rhine-Westphalia. Later his son took over the business and his son also stayed in the farm. A decision that was quite unspectacular back then in the 1990s. Unlike today.

On average, six dairy farmers give up in Germany every day. Of the 85,000 farms in 2012, around 53,600 are still in existence – a third had to close their doors within just a decade.

In Bavaria, the largest dairy country in the republic, farm deaths have recently progressed particularly rapidly. With an average of 49 cows, many of the traditionally small farms cannot withstand the growing financial pressure without farmersbank help.

In Lower Saxony and NRW, places two and three in terms of milk production, the herds are larger. But this is also where many dairy farmers throw up. This is also not uncommon among the Leyschultes’ circle of acquaintances.

For senior boss Hajo Leyschulte it was anything but a matter of course that his eldest daughter would take over the farm. “I still remember when I asked my dad: Would you make me fit for the apprenticeship? That was a very emotional moment,” says Katharina Leyschulte. “It really affected both of us” – only out of joy, her father assures later.

He is not worried about his daughter’s financial situation, the farm is sustainable. “It pays off somewhere, but it’s a small calculation.” The annual turnover of the company is between 600,000 and 800,000 euros, if things go well, you end up with a 10 percent profit, what about farmersbank.

The fact that Katharina Leyschulte’s husband Toni has a good job in logistics takes the pressure off. But together with her father, she works around 100 hours a week, on her own account and at her own risk. Rarely is there really a vacation or weekend. The bottom line number may be black, but for all that, it’s small.

The Leyschultes are broadly based. They grow corn and various types of grain, breed young cattle for sale, and have a large solar system on the roof. They don’t want to rely on milk production alone; despite large herds and current record prices on the milk market.

For years there wasn’t nearly as much money for a liter as it is now: 53 cents. The buyer for their milk is the nearby Mertens dairy, the main supplier to Coppenrath and Wiese. Anyone who has ever had a piece of cream cake from the frozen confectionery in their mouth has most likely been in the Leyschultes’ cowshed with their tongue.

However, reliable sales stand in the way of exploding production costs on the farm. Delivery bottlenecks, inflation and the energy crisis hit farmers with fertilizers, crop protection, diesel and energy. The machines are also becoming increasingly expensive.

In addition, there are increasingly strict climate, environmental and animal welfare requirements, says Katharina Leyschulte. What annoys her the most is the calf transport. “Previously we were able to give our bull calves to the fattener after two weeks. From the beginning of next year we will have to wait twice as long before they can be picked up.”

A law with the unwieldy abbreviation “TierschTrV” is to blame. The Animal Welfare Transport Ordinance now only allows calves to be transported from the 28th day of life. There is still a transition period until the end of December, but the changeover within a year is the smaller problem.

“Each calf has to stay here for two weeks longer and needs feed for two weeks longer,” says farmers Leyschulte. This costs an additional 75 euros per animal. She doesn’t get any compensation for that. “This is paid neither by the state nor by the consumer, but comes from my pocket.” And from the point of view of the young farmer, it makes little sense anyway.

“In the first two weeks, the calves have a particularly good defense against pathogens through their mother’s milk, after which there is an immune deficiency. They are more susceptible and the transport is also more stressful,” she says. You don’t feel that experts from the industry were involved in changing the law.

Back in the cowshed. Leyschulte has been on his feet for three hours now, still with an empty stomach. Breakfast is ready in the kitchen of the farmhouse, mother and grandmother have laid the table, and temporary workers, trainees and interns are also sitting at the table. But the dairy farmer wants to stop by the maternity stall first – three calves were born early in the morning.

Cow Motzi’s twins farmers are standing on shaky legs, Cow Torte’s calf has fallen onto the other side of the barn fence. Katharina Leyschulte helps the calf back onto the straw. His fur is still damp, the big dark eyes look a little glazed at the world.

But the time together is soon over for the newborns and their mothers. Shortly thereafter, they are separated. It is the rule in Germany: Only a small proportion of dairy farms grant their cows parental leave – even on organic farms, togetherness is not guaranteed. Even non-vegans can feel their hearts clench at the thought. The question of costs runs through all areas of court life.

Because the cow-bound calf rearing is often not profitable, the market does not reward the plus in animal welfare. Additional stable costs or pasture lease and less marketable milk would further reduce the yields. “The calves come to daycare very early,” says Katharina Leyschulte. “The cows are working mums, just like me.”

After separation and a short quarantine, the calves live with her in shared flats, and fresh milk from their own herd flows out of the plastic teats in their feeding buckets. After all. Elsewhere, mixed milk powder is fed, which is cheaper and: The early separation is better than a late one. The longer the waiting time, the more the animals miss each other.

Katharina Leyschulte’s ten-month-old daughter plays in the playpen inside. Since the childminder is canceled due to Covid, grandma Birgit and great-grandma Elisabeth take care of the toddler. Eight weeks after the birth, Katharina was entitled to a farm hand. After half the time, her social security phoned to ask if she could go back to work earlier.

“Self-employment farmers for women in agriculture is really tough,” she says. “If I didn’t have my family behind me, I don’t know what I would do.” The way to the kitchen leads past the Leyschultes’ dark blue Hyundai: “Proud to be a Farmer” is written on the rear window, the Tecklenburg license plate spells out “TE-AM”.

Between slices of brown bread and hard-boiled eggs, breakfast is all about the new free trade agreement that Germany recently signed with the dairy nation New Zealand. The deal: better import conditions for German cars in exchange for better import conditions for butter, yoghurt and milk powder from New Zealand.

Father Hajo Leyschulte shakes his head while chewing and stares at the measuring cup with milk in front of him; straight from the milking tank, four percent fat, a hint of barn taste. “For us, that means the German market will be flooded again by foreign competition, which can produce and sell cheaper than us because they don’t have to work under the correspondingly strict environmental and climate regulations. Thanks for nothing,” he curses.

You can’t do more than block the roads, as desperate Dutch cattle farmers recently did. “We also don’t want the population to suffer because we’re protesting,” says Hajo Leyschulte. “It’s really difficult to draw attention to us, the connections are now so complex.”

This also applies to the decision of the EU, which will force farmers from 2023 to set aside four percent of their land for more biodiversity and climate protection . “You can’t explain to a person in the supermarket that we have to shut down areas and that the milk will then be maybe ten cents more expensive .”

The combination of increasingly stringent farmers requirements, ever-increasing costs and what consumers perceive as little appreciation would make many farmers despair. “We lose colleagues every day who break down because of this heck of it.” The Leyschulte senior takes a deep breath, his wife Birgit puts her hand on his arm. Katharina’s daughter is whining in the background.

“Unfortunately, all the work behind the milk product is often not seen,” she says, taking her granddaughter on her lap. She can only hope that family businesses like hers can exist as models. “I thought it was really nice growing up like that. We always get together for meals and joint projects and live here as idyllically as others vacation.”

The farm is located in a nature reserve, all around partridges build their nests, swallows nest in the roof of the farmhouse, the many bees in the driveway make you forget for a moment the serious death of insects in the whole country.

There are many indications that agriculture is largely responsible for some of the most pressing ecological problems, from the death of insects to the climate crisis to the loss of species: too much fertilizer, too much Pesticides, too many animals. The nature conservation organization Nabu warns that today’s form of agriculture is a “nail in the coffin” for animals and plants.

For Katharina Leyschulte, this is the one-sided view of environmental activists, city dwellers and idealistic politicians. “You can see how much creeps, flees and beeps here.” The farms are indispensable for the ecosystem and biological diversity. “But many people no longer understand that it is connected.”

Instead, animal husbandry is becoming increasingly restricted. “Of course we emit nitrogen and greenhouse gases, but we also produce high-quality food , the most important thing the body needs needs!”

Not far from the Leyschultschen Hof in the Netherlands, it shows how far things can go if compromises are not found in good time that do justice to both the environment and the farmers. There the government wants to take away a large part of the animals from numerous cattle farmers.

They will see extreme nitrogen pollution in large areas of the country charged – the factual expropriation seems to be the last way out of the impending ecological collapse. It would be the death knell for many farms.

“Behind companies there are always families who do their job with their heart and soul, take care of their animals and are now being forced to give up because they happen to live in the wrong postcode area.” The young dairy farmer hopes that the situation in Germany will not deteriorate so much.

Here, too, the politicians are desperately looking for a solution for the nitrogen values that are clearly too high in many places. While her parents are politically involved, Katharina Leyschulte wants to ensure more understanding, especially among consumers in a contemporary way on social media. Hashtag dialogue, hashtag dream job.

In addition, up to 600 visitors travel to the farm every year to see what Katharina Leyschulte calls “normal dairy farming”. Or, to stay in the vocabulary of the industry: conventional agriculture, which many critics equate with factory farming. For Katharina and Hajo Leyschulte it is an emotive word. You would like to ban it from the discussion as an empty battlefield.

Animal numbers alone are not meaningful. Just as little as an organic certification – which your company does not have. “Organic is just a seal for me. It says nothing about the quality of the animal husbandry, the milk and the sustainability off”, says Katharina Leyschulte. Her own philosophy has repeatedly placed the family business among the best milk producers in the north.

The “Goldene Olga”, the award of the state association of the dairy industry in Lower Saxony, hangs twice on the wooden paneling of the largest barn. Kardashian, Hanuta, Barbie and the other cows cannot read from the signs that “exemplary animal welfare” is practiced here. But they should feel it.

“We gradually tore down the walls early on, opened the roofs and created more space for the animals. Light and air had to come in here,” says Katharina, being nudged with the snout of a grey-brown cow. Ronja is her engagement cow; the first addition to the family, even before their own daughter.

“My husband knows that I don’t care for jewelry. Instead, he gave me Ronja as a present for my marriage proposal.” She scratches the cow on the cheek. Farm guests are often surprised that their animals are doing well, although they are a conventional farm.

In many minds there seems to be only mountain meadow idyll or cow jail. Both are not representative of the industry in Germany. The fact that the large supermarket chains have been printing an animal welfare label with numbers from 1 to 4 on meat and dairy products for some time does not help.

“We now have an absolute label trallala, the retail trade is doing its own thing, the organic sector the same way. The milk carton is slowly becoming too small for all the symbols and consumers have long lost perspective. And what really all farmers want, we don’t get: a brand Made in Germany”

Austria did it, France also, United Kingdom anyway. Only Germany can’t do it, “because the Ministry of Agriculture is opposed to it.” Katharina is certain: What is an absolute quality feature in washing machines, cars and tools would also help the farmers.

In practical terms, however, farms today need labels for cows instead of their milk. Among other things, for cow 190. There are first names after the first calf, when the female cow has become a dairy cow. Before the external milk inspector stops by in the afternoon, there are ten baptisms.

The Leyschultes collect their ideas in a WhatsApp group with family, friends and colleagues. They have already given hundreds of names. The fact that the cows always have to have the same first letter as their mothers does not make the task any easier.

The junior boss sweeps her index finger through the suggestions, pauses and laughs. “No, Habecki doesn’t work at all. That just doesn’t sound right.” In addition to stars, Pokémon and fairy tale characters, some politicians actually live in the cowshed. Their names, not their politics.

So far, Katharina Leyschulte seems rather disappointed with the new government, She repeatedly emphasizes how much she had hoped for from the turning point in Berlin, The cow with “H” becomes “Hilli”. Even Elfe, Gerti and Meowth have lost their numbers in everyday life. The young farmer’s wife baptizes the 190 on Watt. And somehow “Scholz” also makes it onto the list.